2016 Utah Ties Art Exhibition Review

I was one of ten artists selected to participate in the tenth annual Utah Ties exhibition in Salt Lake City. You can read the Salt Lake City Weekly write up in the link below.

www.cityweekly.net/utah/fit-to-be-tied/…Emily Carr's Health Design Lab and Providence Health Care Team Up to Create a Better User Experience

I worked as a research assistant in Emily Carr University of Art and Design's Health Design Lab (HDL).

HDL partnered with Providence Health Care's research and development group to create prototypes to test at their Brock Fahrni Residential Care Centre. These design interventions will inform future implementations to create an environment of comfort and empowerment for Providence Health's residents.

globalnews.ca/video/2544400/emily-carr-…2015 ECUAD Student Art Sale

Emily Carr's Legendary Student Art Sale. The Vancouver Sun covered the event and I spoke about my sculpture in this clip. The work sold within the first hour of opening night.

www.vancouversun.com/search/Video+Stude…The Fifty Fifty Arts Collective Artist Interview

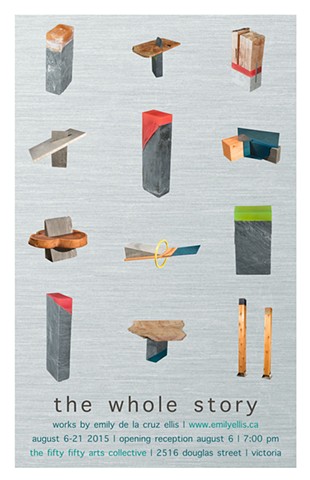

Artist interview for "The Whole Story" show at The Fifty Fifty Arts Collective

August 2015Exhibit Vic Coverage

Emily de la Cruz Ellis at the Fifty Fifty Arts Collective

Victoria, British Columbia

Opening Night Coverage August 6, 2015The Fifty Fifty Art Collective Press

Solo Show Release

thefiftyfifty.net/index.php?action=show…"The Whole Story"

Solo show poster for The Fifty Fifty Arts Collective August 2015

15 bytes The Face of Utah Sculpture Exhibition Review August 2012

Exhibition Review: West Valley City

What You Should Bump Into

The Face of Utah Sculpture at Utah Cultural Celebration Center

by Geoff WichertIn an interview he gave Jennifer Napier Pierce prior to the opening of The Face Of Utah Sculpture, an annual exhibition he founded and curates, Dan Cummings explained why he considers this such an important opportunity for artists like him. “Sculptors,” he said, “don’t much get single shows.” It’s true. Sculptors are typically invited to take part in two-person shows, where their work complements the work of a painter. To be seen clearly, paintings require empty rooms; sculpture ensures the resulting space is not wasted. Thus the celebrated judgment of Barnett Newman: “A sculpture is what you bump into when you back up to get a look at a painting.” But there is good reason why we, as audience, should see what Cummings has brought to the Cultural Celebration Center. Far from the display of challenging aesthetic statements that make up many modern art shows, this one is immediately accessible and, in place of consternation, is more likely to generate feelings of pleasure, fun, and even exhilaration.

Anyone who thinks artists work best in garrets, away from interference by the public, can learn something from the example of Marilyn Sunderland. A few years ago, her painted gourds brought to mind folk arts. Although she selected the gourd as a painter selects a grade and shape of canvas, the final product resembled classroom design practice: fit the image to the 3D shape. Interaction with her peers and the public has opened up her approach, literally: in “The Rope” she cuts away the negative space between coils of illusionistic cordage carved in bas relief, revealing the solid-looking gourd to be a thin, hollow skin.|1| Paradoxically, the more she reduces the solid-looking ellipsoid to a surface of lace, the more solid the representation appears. The gourd’s shape disappears, demonstrating the dimensional alchemy underlying all visual art. Rope connects thematically with “Looking At An Object I’ll Never Understand,” one of Cummings’ fused and carved glass pieces, in which a black-and-white checkerboard resembles water into which stones are thrown, the surface roiling into ornaments suggesting a computer animation of a mathematical equation.|2| Another glass artist, Andrew Kosorok, uses the translucence of flat glass to model the dimensions of space, demonstrating the notion shared among the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions that spirit first creates, and then infuses, everything.

It sometimes seems the three dimensions of sculpture impose more limits on an artist than do the two of painting, but contrasting representations of the human form argue that the range of possibilities in sculpture is as wide as the artist’s vision. Julie Lucus opens up the torso in “Nevermore,” where her signature mosaic tiles suggest the stone walls of a prison or a fortress, a suggestion underscored by the presence of barred windows behind the occupant, who dwells close to the heart.|3| Emily de la Cruz Ellis takes an opposing view in “Don’t Look Back in Anger.” Obdurate and opaque, her sandstone blocks lie silent on the floor, denying entry and suggesting John Donne was wrong: everyone is an island, no one can be known.|4| But Brian Christensen’s “Blue Note” gets it right.|5| Our own knowledge and experience allow us to decipher the features of his standing female figure, who proffers us the crystal she holds in her hand as though it were the key to her sorrow. The ruined piano mechanism that frames her and carves out her space, stopping our eyes from straying, suggests another kind of passageway: the evocative art of music, tinted with aural color the way her skin carries the shifting hints of pigment. Like sounds, appearances can carry something essential between us. There are conduits by which we can know and—sculpture being supremely tactile—touch one another.

No survey of 3-D art could be complete without a few examples of trompe-l’oeil -- in which the sculptor displays his skill by fooling our eyes. In effect, such illusions argue that touch remains more reliable than its more popular, more glamorous, and more successful long-distance version: vision. Relegated long ago to the status of stunt, of trompe-l’oeil, made a comeback when Jasper Johns rendered mundane beer cans in painted bronze, those transformative and supposedly ennobling materials. Perfectly illusionistic tours de force followed, including leather goods made of clay and a motorcycle carved from wood. Darwin Dower has also chosen wood, but a more homely and more challenging array of subjects. “Restoration: A Divine Calling” reveals what a desktop was before the computer undertook to steal its identity and displace so many once-familiar things. Among the objects and materials it ‘restores’ are leather bindings, printed paper pages, spectacles, a candle, and the compound paraphernalia of handwriting: a feather quill, an inkstand with cover, a blotter, and a bit of foolscap displaying a fine hand.|6| There can be a fine line between pleasure and frustration, and as the eye wanders along the ragged edges of well-worn paper pages, the mind crosses back and forth between the imaginary pleasure of turning over those pages and the frustration of knowing it to be impossible.

In the same way, the limit of art is also what makes it indispensable. Only in our imaginations can we go where these works take us, or make us want to take ourselves. Not every one of the 70 works by 40 artists assembled here will succeed for everyone, but each is a potential launching pad for a trip into real things and their imaginary connections. Instead of selecting a narrow range of objects meant to prove a point, The Face of Utah Sculpture assumes that if it includes the wide range of competent work, viewers can sort them out. You don’t have to like them all, but if Andrea Heidienger’s cast-paper cityscape is not to your liking, perhaps Randy Chamberlain’s bronze bald eagle in the form of a scythe will do. But take a second look at the things you first want to dismiss: therein lies the key to personal growth.

The Face of Utah Sculpture VIII is at West Valley City's Utah Cultural Celebration Center through August 16.